Many thanks to Preston Evans, Aaron Li, Jordi Baylina, Shashank Agrawal, Ventali Tan, Daniel Lubarov and James Stearn for feedback.

Outline

- Introduction

- Why Proof of Stake (PoS) might not work

- Proof of Efficiency

- Proof Generation Outsourcing + MEV Auction

- Future work

- Conclusion

Introduction

The scalability problem that has faced Ethereum influenced a phase of innovation that brought us three new products: state channels, plasma channels, and then finally zk-rollups. State channels allow participants to make an arbitrary number of transactions off-chain, with the only on-chain transactions being the opening and closing of the channel. To open a channel, a multisig smart contract is deployed, and then users submit funds for lock-up to be used off-chain. The smart contracts then verify the submitted final state, and disperse the funds at closing. The state that is submitted is usually the last agreed-upon state of the channel that has both parties’ signatures. Beyond this final state, all other transactions can happen off-chain. This makes this method incredibly scalable, but it still has some limitations. Namely, the initial lock-up of capital, and a fixed number of participants that cannot be changed throughout its lifetime.

In response, Plasma channels were invented. They are managed by smart contracts that store merkle trees of the transactions that occur off-chain. At the end of every interval, an operator needs to submit a merkle tree that includes the new block of transactions from the interval. Blocks are not finalized till the end of a determined challenge period, usually 7 days. This solves the limitations mentioned above on state channels, but raises another concern that there is now a cost per transaction, due to the updating of state after every interval, whereas in state channels the only state update would occur at closing. Both solutions also share a data availability concern, that users (for a state channel) or operators (plasma channels) are expected to store valid state off-chain, and not lose them due to error or mechanical failure. Hence zero knowledge rollups were born. Rollups move computations and state storage off-chain but still store some data per transaction on-chain. This data per transaction comes in a highly compressed form, so as to still give the benefit of drastically reduced gas costs.

A lot of new projects have emerged in the zk-rollup space since its inception, each of them ambitious and hoping to be the “ultimate” solution. However, as it is with every rapidly growing technology there are certain aspects that may be overlooked, in order to facilitate fast execution and entry to the market. We will be doing a deep dive into what we believe is one of those aspects: “decentralization”.

All current zk-rollups are centralized - some do not even have a projected path to decentralization1. This is definitely not an ideal situation to be in. Some characteristics of a truly decentralized zk-rollup which we hope to achieve2:

- Safety / Soundness. Ability to resist a malicious party from taking control over the network, and dictating the present and future state of the network.

- Censorship resistance. Everyone must have access to the network and interact with other participants. The network should not be able to deny this right to any individual. It also needs to be be possible for users to withdraw their funds back to L1 or force execute transactions in L2 by paying gas in L1, even if the network is compromised, or the operators are limiting user activities on the network.

- Low node / network participant requirements. Individuals should be able to build and run their own node, prover or sequencer without an unreasonable amount of difficulty. Expecting state of the art or highly specialized equipment and high compute resources needs to ve be avoided.

- Economically aligned incentives. Participants should be rewarded equally for upkeep of the network, in order to encourage new participants to enter.

- Liveness. Honest messages should always be included and available to block producers. Chances of halting or lapses in network availability have to be mitigated.

Why Proof of Stake (PoS) might not work

Currently, zk-rollups have a centralization in the block creator. To decentralize the block creator, a question is raised on who we decide as the leader / coordinator for a given block.

There are multiple answers to this question (some we will discuss further in this article): MEV Auction, Burn Auction, Proof of Efficiency and finally Proof of Stake. Most know Proof of Stake from their implementation in L1 blockchains such as Ethereum, but they can also be used in zk-rollups for leader election with some teams actively working on this: Polygon Zero, and Starkware.

However, there are some concerns to using Proof of Stake in rollups, as explained by one researcher3:

The problem with integrating PoS into a zk-rollup is that you are unable to do a hard fork, which provides most of the security guarantees in L1 implementations. This makes it susceptible to DOS and Fake DOS attacks.

Mentioned in the quotation above, a denial-of-service attack happens when a sufficiently large group of colluding validators with a lot of stake tries to leverage it through a manipulative manner to reap some sort of reward. This basically allows them to have full control over the transaction flow in the rollup (they still cannot forge transactions from addresses due to the zero knowledge nature of the rollup). They could:

- Charge high fees in order to include transactions in the block.

- Censor all network transactions by minting empty blocks. If they have a short position on the network token of the rollup, this could give them profits, as users dump the token since it no longer has any use.

- Lock up supplies of certain tokens. This allows them to reap economic benefits from liquidity pools of said tokens.

In addition to these DOS attacks, there is also a slashing attack to consider. This is possible because of the slashing condition that punishes stakers who do not create a block within a specified time X. If a block producer refuses to include transactions from other block producers, even with blocks containing their own transactions, in favor of uncling4 them the stakers will get slashed. If the block producer conducting this attack has a combined active stake with at least a ⅓ of active voting power, then this could be an effective, with-standing attack. Otherwise, it would be fairly rare for a small staker to get two blocks in a row, so it would not have much effect in the long-run. Overall, this would be considered a griefing attack, in that there isn’t an obvious benefit to the attacker, but the attacker could cause harm to their target.

Proof of Efficiency

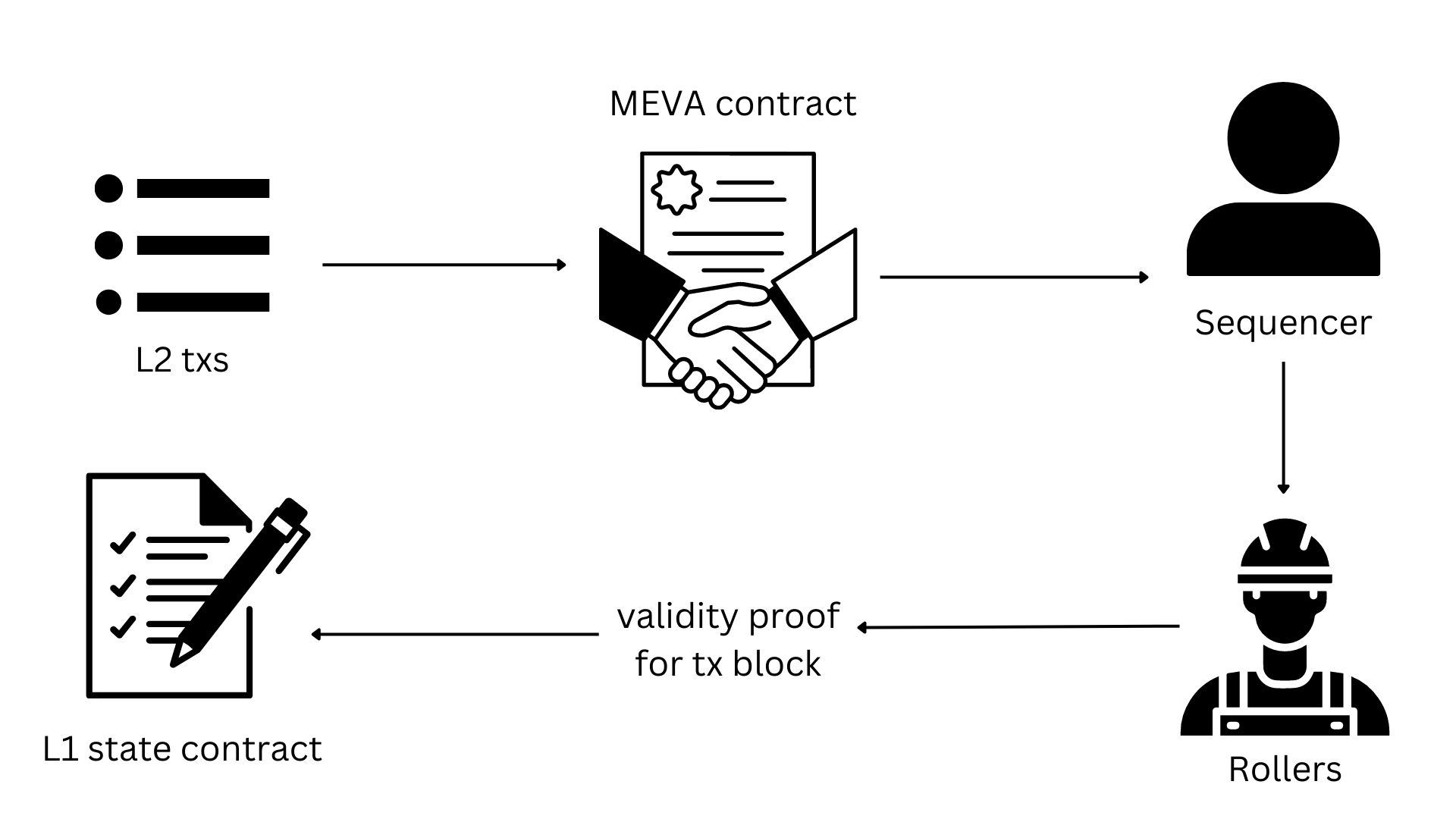

Proof of Efficiency is a new consensus mechanism put forward by a cryptography team on the forum Ethereum Research5 to solve the criticisms of PoS on rollups. It involves a two-step model that splits activities between a sequencer and an aggregator. An overview can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Demonstration of Proof of Efficiency validity proof submission.

A sequencer is responsible for pre-processing and posting L2 transactions to L1. This is done by submitting a transaction on L1 that has the details of the L2 transactions in the calldata field. The sequencer has to pay the L1 gas fee as well as an additional fee in the network token to discourage bad actors. This usage of calldata has certain storage limitations to be considered as well. Even with the intense amount of optimizations it has been through it can only store a limited number of transactions. The average Ethereum block uses about 80KB of data, and if the new EIP-4844 proposal is approved and deployed, the calldata (blob) field could provide on average 1MB of data.6 This means the base layer could theoretically support a 10X in throughput from rollups. This is not including compression techniques that could potentially give space savings of up to 60%7.

There is also a misalignment with this reward and cost structure of the sequencer, as they get charged for the cost of posting the calldata but get rewarded by the L2 gas their transactions generate, which in turn encourages sequencers to favor gas-heavy transactions over simple transactions. During times of network congestion this means that simple transactions may become deprioritized and postponed for an indefinite time, no matter its importance to the user. A solution to this would be to implement a fee structure, where there is a base fee and tip (irrespective of the gas of the transactions). The tip would represent the importance of the transaction to the user and would be the reward for the sequencer for including that transaction. This allows a prioritization of transactions based on importance to the user, rather than a crude one of gas.

Another point to mention is that any individual can become a sequencer by posting the L1 transaction. This does have benefits in terms of censorship resistance (if another sequencer refuses to process someone’s transaction, they can just submit their own transaction), but it does come with some drawbacks. One is that due to this uncoordinated nature, it may not be obvious as to which sequencer one should submit their transaction to, in order for it to be confirmed quicker, taking into consideration that larger batches are more likely to be confirmed by aggregators quicker, and that some aggregators may wait to pool more L2 transactions before posting to L1 in order to reduce the per-unit gas cost.

In the original post formalizing Proof of Efficiency8, the action of sequencers posting the L2 transaction data on L1s could open up the possibility for an inter-sequencer MEV attack. An observer of the L1 mempool can track L2 transactions as they come in, and if they identify a transaction that is of potential MEV value they can submit another L1 transaction with the same L2 transactions in the call data but now with the desired order / inclusion of transactions and a higher gas tip. This means that the attacker’s transaction would be accepted before the honest sequencers’, resulting in the sequencer losing out on the reward of L2 gas, and having to pay for L1 gas without any reimbursement. Researchers have been actively working on solving this risk and have since devised some potential solutions9.

The post also mentions that once the sequencer has posted the transaction information on L1, it now becomes the new virtual future state. In order for this to be confirmed, a validity proof must be submitted on L1 by an aggregator. This soft-confirmation by the virtual state, allows there to be a higher TPS, and lower block interval time. Without this soft-confirmation block interval time would be lengthened to the time taken to generate a proof, which is around 10 minutes10, and coordination between provers would constrain throughput as there is no ordering of transactions that is decided on. This is conducted on a “first come, first accepted” basis, in that the aggregator who submits the proof first will be rewarded by the L2 transaction fees. This race format is concerning in that it encourages centralization around the fastest aggregator, which is the one with the most compute resources.

The MEV Inequality Problem

Overall, there is also an MEV inequality problem that appears through this separate tiered approach between the sequencer and aggregator. This problem comes from the idea that block producers have a lot of power over the ordering, inclusion and exclusion of transactions which gives them the opportunity to benefit from arbitrage opportunities that may originate from DeFi, ICO transactions. This revenue gained from what we call MEV (Miner or Maximum Extractable Value) is seen to rival that of the revenue generated from transaction fees.

The problem is that this high revenue is solely enjoyed by the sequencer, and the aggregator does not get any information or access to this revenue. In some implementations, as described in the Proof of Efficiency proposal, sequencers pay aggregators a proving price to generate a validity proof for a block, and through market dynamics we can ensure this would allow for aggregators to cover costs and then some. But in a more optimal world, what we want since aggregators are the more performant and compute heavy party in the system, is to be rewarded proportionally with sequencers. Funneling more rewards to aggregators may help to reduce finality time, increase proving capacity in the network and encourage more decentralization within the aggregators.

Proof Generation Outsourcing + MEV Auction

Another approach that has been put forward by another cryptography group, is to combine proof generation outsourcing and MEV auctions into a new, overall consensus mechanism11. The focus of proof generation outsourcing is to decentralize proof generation by outsourcing it to “rollers”. Then, after this is successful, the sequencer (block proposer) is decentralized through MEV Auction. See Figure 2 for a visual representation.

Figure 2: Transaction flow from executing on L2 to confirming on L1.

Proof Generation Outsourcing

In this new consensus mechanism put forward, in order to participate in this process, a roller needs to first deposit network tokens into a smart contract. A reputation score is then calculated for each roller based off of the deposit amount and performance history. A centralized sequencer receives transactions from the L2 mempool and generates a new L2 block. It will then randomly select multiple rollers for each block depending on the calculated ratio score. If the roller sends an invalid proof it will be fined, or if the roller sends the proof later than a time T, its reputation score will be decreased. However, if the proof is valid and sent in a time less than T, it will be rewarded. The sequencer will then aggregate all the proofs from the different rollers and upload the proofs to layer 1 for verification.

This approach has a benefit in that it adopts a collaborative format rather than a race format. This allows for reduced wasted compute resources but it also helps for decentralization, as it is moving away from a “fastest prover wins” goal, which causes centralization around the fastest prover. The act of parallelizing proof generation across multiple rollers for one block, helps to lower the barriers of entry to being a prover, making it more accessible for someone to run their own node as they might not need to invest as much into equipment.

This trend towards decentralization is contrasted by the calculation of the reputation score, which is predominated by the deposit amount. If a roller deposits a larger amount, he is more likely to get more proofs to generate. If this lasts over an extended period of time, it would cause resources to be sucked away from smaller rollers (lack of rewards), causing a cycle which may result in the network becoming dependent on a select group of rollers. A potential solution could be to elect rollers with probabilities based on reputation and then send work to the elected rollers at random. This form of selection is not uncommon in other types of protocol implementations12.

A federated prover network13 has similar motives as proof generation outsourcing, by encouraging decentralization. This is where a large block is separated into smaller blocks, which is then broken down into even smaller blocks until you are left with mini 2x2 blocks. The proofs are then generated for this root node (imagine a tree forming, with different layers), and then recursively proven with its neighboring block. This process is repeated until you have a recursive proof for the entire block. In practice, this breaking down process, and building the proof back up from the root takes an immense amount of communication and coordination between the different provers, so much so that it might be more efficient to instead have a few centralized provers.

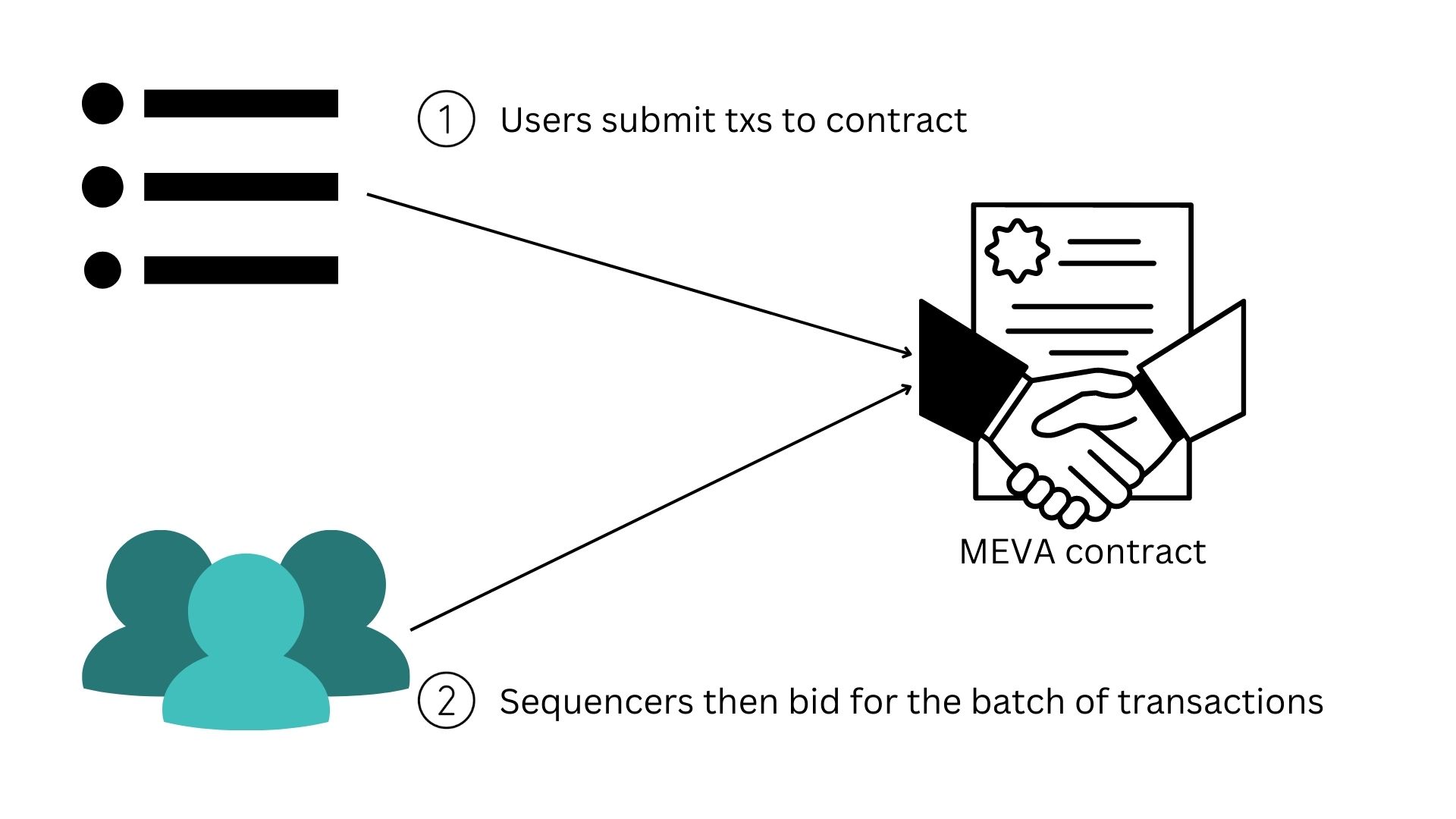

MEV Auction

The MEV Auction (MEVA) was created to solve the issue that sequencers solely benefit from MEV revenue (mentioned in the MEV Inequality Problem above). MEVA allows other participants in the network to benefit from the new revenue source instead of just the block producers14.

MEVA functions through a smart contract that auctions off the right to reorder transactions within an N block window to the highest bidder. In this process, block proposers submit transactions to the MEVA contract and then this contract designates a single “sequencer” at a time to order the transactions, and publish the block. Block proposers in this model would generally be repurposed L1 miners. See Figure 3 for a graphical representation of this process.

Figure 3: Diagram of MEV auction process.

Staying true to its origins, the main benefits from this approach is that the winning bids deposited into the MEVA contract from the auctions can then be used to reward rollers for the blocks they have proven, or to fund public goods on the network - there are a lot of possibilities.

However, there are certain limitations with this approach that need to be considered. Firstly, there is a possibility for collusion between the sequencers during the auction process. This could lead to artificially low bids, reducing revenue to the network. Another concern is how to set up the auction for long-term stability, regarding specifically two parameters: duration of time slot, and penalties to reduce the risk of bad actors. The time slot must be large enough to provide economic benefits to the sequencer but must also be low enough so that the health of the network is not compromised if the sequencer is indeed a bad actor. And the penalty must be in proportion with this economic benefit that is provided to the sequencer throughout the time slot in order to discourage bad behavior.

Future work

Listed below are some potential directions that we could see the space move towards, that are good thought experiments to test our understanding of what is possible and encourage fruitful discussion. They mainly aim to solve the limitations in Proof of Efficiency and Proof Generation Outsourcing + MEVA, that we have outlined above.

MEV Auction + Single Block Creator

One aspect of the Proof Generation Outsourcing + MEV Auction approach that was overlooked in our analysis is, the coordination between the sequencer that has won the MEV auction and the decentralized network of provers. There is currently no perfect solution for a sequencer to communicate the block being made to provers whilst avoiding malicious front-running and data withholding possibilities. This is why we propose a new direction that keeps the sequencer and prover in the same entity and then combining that with a variation of an MEV Auction.

The difference between this variant and the traditional MEVA outlined above is that instead of an MEVA smart contract, the sequencer gets picked randomly, and solicits bids from block producers. The sequencer gets to keep some percentage of the bid that he accepts, and the rest goes into a smart contract for distribution to reward participants of the smart contract. This way, the chain isn’t forced to always accept the highest bid. During a DOS attack, the sequencer can easily accept a lower bid that actually includes transactions. And since sequencers are chosen randomly, at least some of the time we expect them to do this, since many sequencers will value the liveness of the chain more than a small increase in their share of the revenue.

But, there are some drawbacks to this proposal too, since malicious sequencers could in theory withhold blocks (violating liveness for the time period the sequencer is allocated). Also, the time taken to generate the validity proof that is uploaded to L1 would be the block interval time, as there is no soft-commitment of transactions. This proof generation time can be around 10 minutes, which is the opposite of what is expected from a low-latency, high-throughput zk-rollup.

Optimistic Pipeline

An alternate direction to avoid the long block interval time is to post a soft-confirmation before processing the validity proof for the block. However, to avoid the limitations of the calldata storage, instead of including the raw transaction details in the calldata field, the root commitment and state difference are processed. Afterwards, when the validity proof is generated it is uploaded to L1, the block is finalized. The main drawback is that if the block proposer does not follow through with the proof after posting the commitment, this would disrupt proposers from building future blocks, making their work invalid and halting the network as no one else has the perfect information of what the transactions were. We put forward an open question to the community if there are any safe-guards we can add to this approach to mitigate this malicious sequencer risk.

Conclusion

ZK rollups have definitely made great progress from its early primitives of plasma and state channels, now providing users with the highest guarantees of security with the increased throughput as well. The main challenges that lie ahead for ZK rollups can be categorized into:

- MEV equality

- Decentralization of block building.

- Incentive alignment for all network participants.

These challenges are important to focus on, as the technology reaches mainstream adoption - which is also why ZK rollups in a unique situation. For the first time, decentralization plans were made after network adoption. The potential ramifications to existing users from errors and technical oversight could create a difficult situation. Hopefully, in the coming years, we can see ZK rollups provide all the ideal, decentralized characteristics that we laid out in the introduction.

If you are a zero-knowledge proof or cryptography expert interested in further discussions or working together on this subject, please reach out to me at ibrahim@delendum.xyz.

Footnotes

-

Centralized mainly pertains to the permissioning of the sequencer. ↩

-

[Articles that inspired this list of characteristics] https://jumpcrypto.com/a-framework-for-analyzing-l1s/, https://hackmd.io/@yezhang/SkmyXzWMY, https://ethresear.ch/t/proof-of-efficiency-a-new-consensus-mechanism-for-zk-rollups/11988. ↩

-

[Post on the concerns of Proof of Stake in rollups] https://ethresear.ch/t/against-proof-of-stake-for-zk-op-rollup-leader-election/7698 ↩

-

An uncle block is a block that the following validators didn’t build on top of, so it doesn’t become part of the canonical chain; it just lives on an abandoned fork. In this scenario the “uncling” would be intentional/nefarious, but in other cases it can happen just because a block didn’t propagate through the network quickly enough. ↩

-

Proposal by Polygon Hermez team of Proof of Efficiency] https://ethresear.ch/t/proof-of-efficiency-a-new-consensus-mechanism-for-zk-rollups/11988 ↩

-

[Notes on EIP-4844] https://notes.ethereum.org/@vbuterin/proto_danksharding_faq#What-is-Danksharding ↩

-

[Article by Optimism Foundation detailing calldata compression methods] https://medium.com/ethereum-optimism/the-road-to-sub-dollar-transactions-part-2-compression-edition-6bb2890e3e92 ↩

-

Proposal by Polygon Hermez team of Proof of Efficiency] https://ethresear.ch/t/proof-of-efficiency-a-new-consensus-mechanism-for-zk-rollups/11988 ↩

-

The Polygon Hermez team has put forward a solution to this attack that is not mentioned in the original proposal. It is to implement a ChainID function that is specific to each sequencer, and is included in the signed transaction, so that a user only ever authorizes one sequencer (and only them) to execute a transaction, thereby mitigating the chance of a sandwich attack by another sequencer. ↩

-

[Proving time for zkSync rollup] https://docs.zksync.io/userdocs/tech/#zk-rollup-architecture ↩

-

[Notes on Scroll’s decentralization plans which includes details on decentralized prover network mentioned] https://hackmd.io/@yezhang/SkmyXzWMY ↩

-

[Harmony’s Effective Proof of Stake] https://docs.harmony.one/home/general/technology/effective-proof-of-stake ↩

-

[Aztec’s talk on overall rollup decentralization ideas and federated prover network] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rU7EBP3FbNg ↩

-

[Proposal of MEV Auction] https://ethresear.ch/t/mev-auction-auctioning-transaction-ordering-rights-as-a-solution-to-miner-extractable-value/6788 ↩