Many thanks to Yupeng Zhang, Daniel Lubarov, Carol Xie, Gautam Botrel, Ventali Tan, Albert Vučinović, and Miroslav Jerković for feedback.

Table of Content

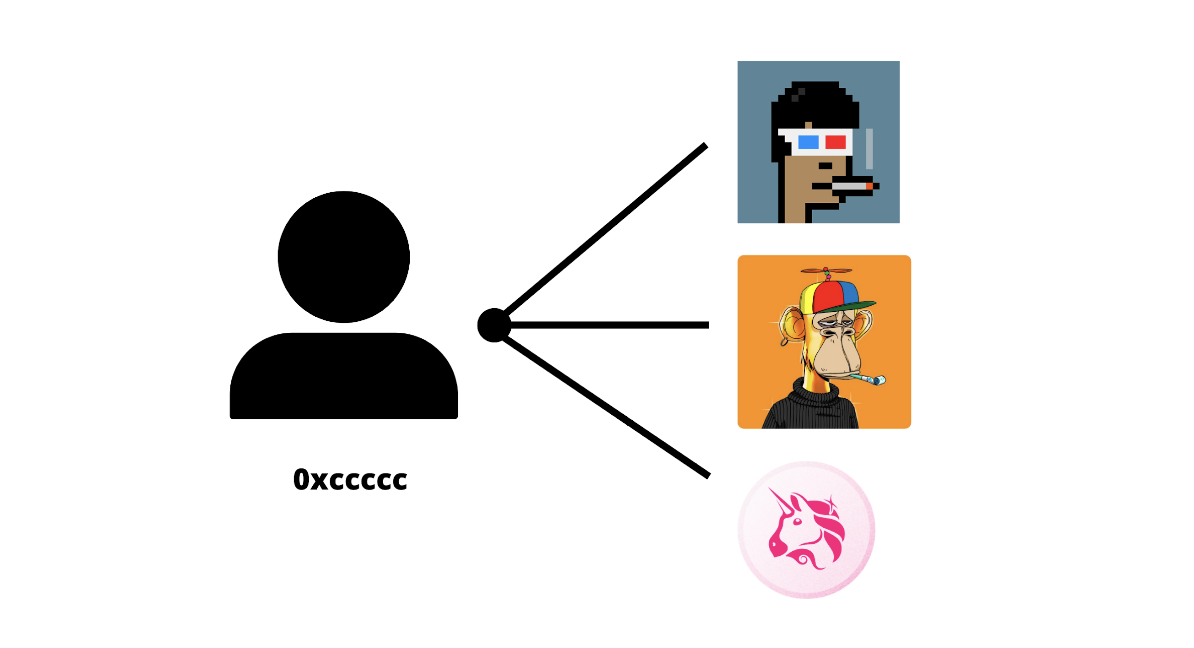

In the blockchain world, identity could manifest in multiple ways. A real-world identity like a person or an organization can take different forms on one or more blockchains, and an identity on the blockchain can represent several real-world entities. Such identities could be established through the possession of private keys, ownership of special types of NFTs, participation of a certain type in DeFi, etc., or even a combination of these.

Figure 1: Demonstration of digital identity

Such a versatile and flexible notion of identity can enable use-cases and experiences like never before — but we need to be mindful of privacy too! Someone’s identity could be multiple things interconnected in a specific way, but only a certain part of it may be important in a setting. For instance, the organizers of a concert that only allows BAYC NFT holders to attend don’t really care which of the 10,000 NFTs you own as long as you own at least one of them. Participation in a DeFi conference may require that you have lent out 50k tokens on a certain DeFi exchange last year but not exactly how much you lent out, how long you participated, etc.

First Example

Zero-knowledge (ZK) proofs could really enable such use-cases while providing the best possible mathematically-provable privacy for the identities involved. To elaborate on this a bit more, let us go back to the two examples in the previous paragraph. For the first example, a ZK proof would show that a person P who wants to attend the concert knows the secret key of an address A that belongs to the set of 10,000 addresses of the BAYC NFT holders. Breaking it down further:

- the public input is the set S of all addresses that own the tokens (NFTs) at a certain height in the chain (see BAYC’s contract here);

-

the private input of P is a secret key sk1; and,

- the statement we want to prove in ZK is that the address derived from sk is in the set S.

In the zero-knowledge academic literature, proofs of this kind are typically called membership-proofs. There are several ways to generate such proofs. If the set is not too large, one could use an RSA accumulator2.

With an RSA accumulator, the set S can be represented with a short value – and the membership proofs are also short. Addresses can be added or deleted from S at low cost too, independent of the number of values accumulated. However, the time taken to accumulate the set S and to produce proofs could be linear in the size of S in the worst case (actual time bounds depend on the specifics of the setting and could even be constant-time). There is another twist here: not only do we want to prove that a certain address A is in the set but also that A is derived from sk, which is usually a group operation followed by the application of a hash function. Custom ZK protocols can be designed for the former (e.g., knowledge of discrete logarithm) but a general-purpose ZK system is usually best suited for the latter. Yet another problem would be gluing the three components together in an efficient way (membership, discrete log, and preimage of hash); see this for instance.

Second Example

The second use-case mentioned above is a bit more complex than the first. The person interested in participating in the DeFI conference needs to show that they sent a transaction tx to the blockchain in question (like Ethereum) which invoked the lending function in the DeFi contract, say DF. They also need to show that tx transferred at least 50k tokens and it was added to the blockchain between the two blocks that correspond to the start and end of 2021. Now, depending on the blockchain, hundreds of thousands of blocks may be generated in one year. Each of these blocks contains a hash of all the transactions included (usually called the transaction hash). A ZKP could be used to show that tx is “contained” in the transaction hash of a certain block B — without revealing tx itself — but that would reveal a lot more than we want to. In the extreme case, if B contains only one transaction for the contract DF, then the ZKP is meaningless. Ideally, we should like to show that tx is contained in the transaction hash of one of the blocks from the year 2021.

Generating a Merkle tree containing all the blocks from 2021 (or at least the blocks that have some transaction for DF) and proving that the block containing tx is just one of the leaves of the Merkle tree would be a more scalable approach here. So, for this problem:

- the public input is the Merkle root of the set of all blocks from 2021 (or at least the right subset of them) and the code of contract DF (referenced through the contract address on the chain);

- the private input is the secret key sk used to sign tx, tx itself, block B that contains tx, and path of B in the Merkle tree; and,

- the statement we want to prove is that sk was used to sign tx, that tx is contained in B, that B is part of the Merkle tree, that tx invokes the appropriate function in DF, and that tx transfers at least 50k tokens (other parameters of tx should remain hidden).

We are merely scratching the surface of a broad array of identity assertions that could be made in different use-cases, and the ZK statements have already begun to show some complexity. In fact, they would become even more complex once we start to think more concretely (admittedly, the statement for the DeFi conference participation problem above is rather simplistic). Some of the complexities include:

- DF was not called directly but through another contract or a series of contracts;

- tx was included in the blockchain but didn’t have the desired effect on DF’s state;

- the conference cares about the actual dollar amount lent at today’s rate, not the tokens.

Thinking outside the box

We need not worry too much though. The beauty of ZKPs is that virtually any statement that you can think of can be proved in zero-knowledge (to be precise, any relation that can be verified in polynomial time can also be proved in zero-knowledge; stronger results are also known). While the non-interactive version of ZKPs are most suited to address confidentiality, privacy, state-growth, integrity, etc. issues on L1s, interactive proofs may make a lot of sense for many applications where blockchain-based identity assertions are needed.

Figure 2: Example of interactive version of ZKP

The concert admission example above can be used to illustrate the point. There would just be one well-identified verifier for the ZK membership proof of NFT ownership (organizers of the concert who could very well choose to verify off-chain), as opposed to the hundreds or thousands of unidentified verifiers in a typical L1 setting. A prover can actively engage with the verifier and exchange several messages over the course of a session, breaking free of the inherent complexity trade-offs of non-interactive ZK proofs. Indeed, proofs don’t have to be short or the verifier complexity low, so the spectrum of ZK proofs beyond ZK-SNARKs (most popular kind of non-interactive proof system, which also has succinct proofs) can be fully explored. We would be able to make use of proof systems with much better prover complexity, underlying security assumptions, etc.

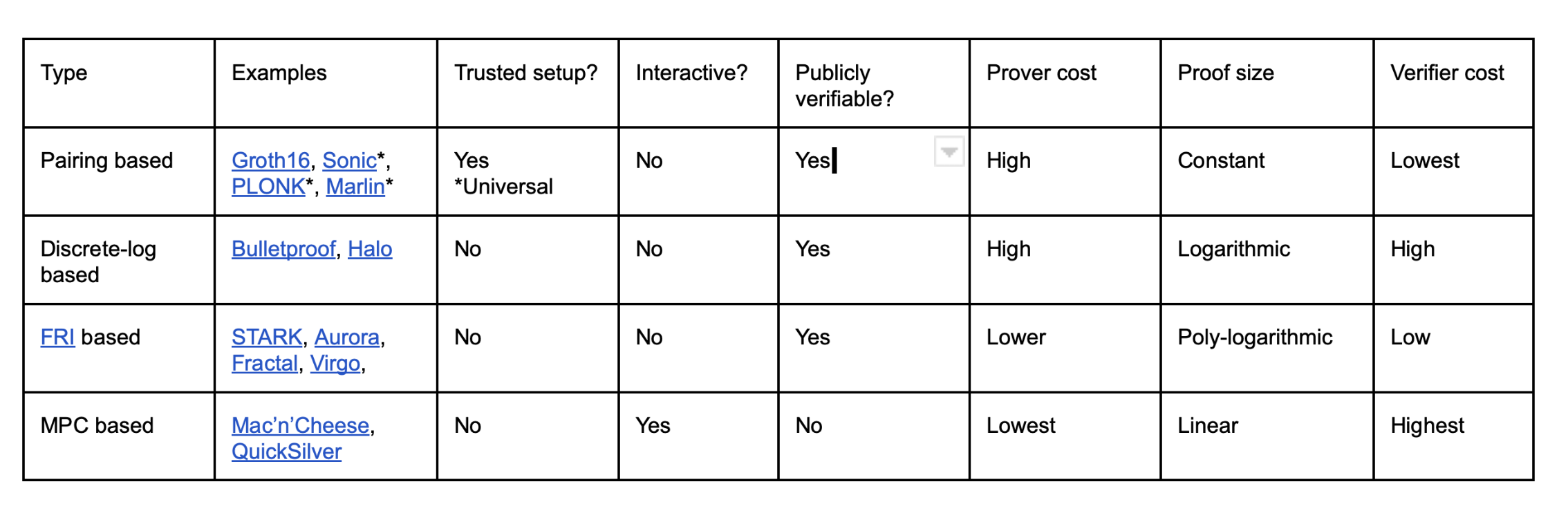

Please see the table below for a high-level comparison of different proof systems. As we go down the table, prover complexity and security assumptions get better while the proof size gets worse. While MPC-based ZK proof systems offer the best prover complexity and don’t need a trusted set-up, proofs are interactive and work for a specific verifier only (the one a prover interacts with), which may not be a problem when identity assertions have to be made to a specific party off-chain. (Several other characteristics of ZK proof systems like post-quantum security are not captured in the table.)

Table 1: High-level comparison of different proof systems

*The table should only be used for some basic guidance and not to make any serious product/business decisions. Within a category itself, ZK systems could have different characteristics and can vary in performance quite a bit. The table is also NOT meant to capture all ZK systems but just some subset of them for illustrative purposes. We apologize for any glaring omissions.

To conclude, identities in the world don’t have to be either blockchain-based or non-blockchain-based. Going forward, they can certainly be a combination of the two — and that would make privacy-preserving identity assertions even more interesting!

If you are a zero-knowledge proof or cryptography expert interested in further discussions or working together on this subject, please reach out to me at shashank@delendum.xyz.

Footnotes

-

If the secret key is not readily available or exportable, one could also produce a signature under the secret key (on some “fresh” challenge) and additionally show that both the signature and the address are generated from the same key. ↩

-

See Zerocoin, a precursor to Zerocash/Zcash, for another interesting application of RSA accumulators. Provisions, a proof-of-solvency proposal for exchanges, takes a different approach for their proof-of-assets protocol which is also a type of membership problem. ↩